![]()

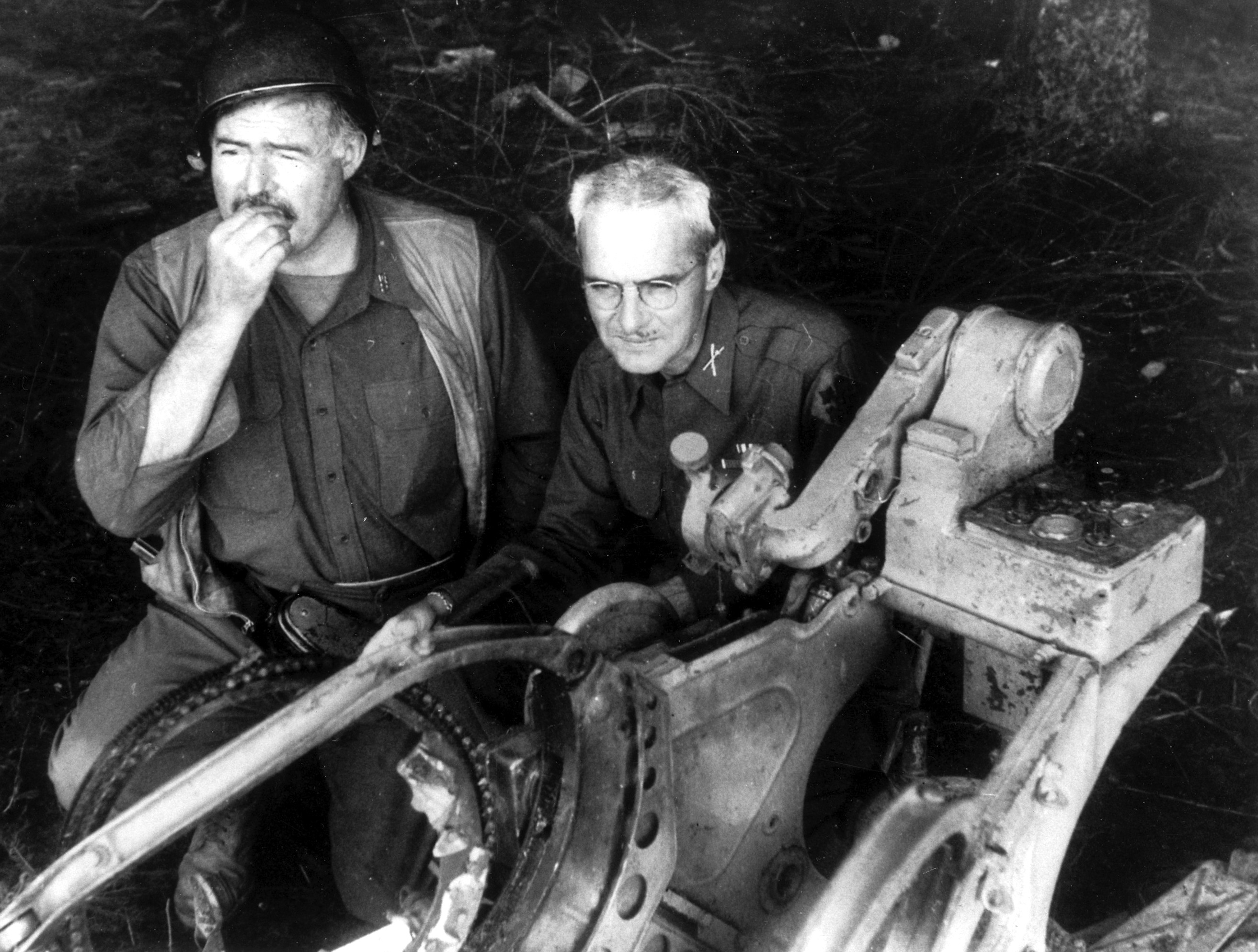

Still from accompanying video (below), edited by Miles Lagoze and Eric Schuman.

A few weeks before our unit’s operation started, Lance Corporal Loya and I stood over a wadi, waiting for each other to throw our cameras down into its dusty, hollow trench. Wadis—the streams or natural ravines that farmers in the region often used as irrigation canals—were our generation’s rice paddies; they were everywhere in Helmand Province. When they weren’t wet, it was comforting to climb inside them—womblike slits in the ground to curl up in and shoot out of. They were the last thing some of us would see before dying. Like feudal tendrils etched across the fields, the wadis in the Sangin Valley were fed by the Kajaki Dam, which provided the area with a (very) limited source of electricity. It was also the main source of water for all the nearby poppy fields. This was September 2011, and guys were already talking conspiracy theories about how the pharmaceutical industry was behind the war, how they were funding the whole thing with the aim of getting us hooked on opioids once we got back to the States all fucked up and traumatized.

I looked down into the wadi where, amazingly, there crawled a tiny desert crab—“shit crabs,” we called them, because everything was shit—and, as a matter of compulsion, I crouched down to get a shot of the little guy before we disposed of our cameras.

“We’ll say we dropped them while we were getting shot at,” I said, standing back up.

“I dunno,” Loya said. “Both of us? That seems fishy.” Loya was the other combat photographer for the First Battalion, Sixth Marines. He was a very spiritual guy, in the sense that in high school he would drop acid and take ecstasy in the deserts of El Paso, and he felt the presence of God with such assuredness that he could convince you, too.

“Maybe one of us should drop ours, and the other should get theirs crushed by an MRAP or something.”

We wanted to break our clunky DV tape recorder cameras so we could get issued the new digital ones that the Marine Corps had just transitioned to. That was how the military worked: you couldn’t get new shit unless the old shit was broke. Ours took forever to export and the footage looked all grey and washed out. We wanted the new digital cameras that made the war pop, to bridge our cinematic dreams of combat with the real thing, and render flat the things that were trying to kill us. They came with night vision infrared; with the click of a button we could turn the world inside out, and make evidence-based war porn the way it was supposed to be seen. To enhance the footage, we even toyed with adding fake muzzle-flash F/X, even though, 95 percent of the time, we didn’t have a clue where we were getting shot from. We didn’t want it to look like we were just shooting into an empty cliff wall, or a mound of dirt, or a house (which, most of the time, we were).

It’s not like we were real journalists anyway; we were propaganda stooges. Loya and I had both enlisted in 2008 as Combat Camera, a small division of the Marine Corps that consisted mostly of guys who’d seen Full Metal Jacket a couple too many times, and didn’t want to have to actually kill anyone. There were usually one or two combat photographers with each infantry unit, so probably ten or fifteen of us total in Helmand Province when we were there. Our main job was to show the benevolence of our troops abroad: building schools and wells, et cetera. Sometimes we’d shoot stuff for Civil Affairs or Psychological Operations as propaganda for the Afghans to come to our side—photos of us playing soccer with some kids that they’d drop from the sky onto a village we were about to invade.

Usually, the purpose of Combat Camera, once you were on the ground and actually filming stuff, was not entirely clear. If you needed to get an interview with someone, their first question would usually be, “Where’s this video gonna go?” I often wouldn’t have the answer. If you were lucky, your video would get broadcast on AFN, the American Forces Network, a news station created by and for the military. AFN was mostly seen as a joke or just ignored as it played in the background at mess halls on air bases in Bagram, or Italy, or Kurdistan. “Today, airmen with the Eighteenth Wing stationed on Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Japan, got a special treat,” I once had to narrate. “A volleyball match between Japanese police officers and air force MPs. What started out as a serious competition soon turned to laughs, as Okinawan locals joined in on the fun …” You wouldn’t know America was at war if you were tuned in to AFN.

Most of the footage just got shuffled into a database so that some colonel working at a desk in Quantico could get a glimpse of what the war was looking like on the ground. If it was deemed suitable for public release, it would get uploaded onto the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service at DVIDShub.net, where you can find an endless stream of Christmas and Thanksgiving shout-outs from soldiers and sailors wishing their families back home a merry Christmas and happy holidays from Afghanistan.

If our footage ever did make it to the civilian news it was usually when there was a firefight, but everything had to be super whitewashed—no images of casualties, no marines cursing, no smoking, et cetera. We had to look professional.

But Loya and I had a side hustle going on. We were filming something besides the fake war we were supposed to be recording and the real war that no one cared about: our own, alternate movie war. And with the switch to digital, anything seemed possible. What we wanted most of all, what we thought would elevate our secret war movie, was to capture, just once, the enemy getting gunned down in crystal clear, 4K high resolution—a real Bigfoot, UFO type of moment. Most of the war footage we had seen was too localized, not expansive enough. You could never see the bad guys until it was too late, after they’d been killed and left as carnage in the gray and dusty archives of Google Street View: War.

We’d sit around stoned, imagining the heaps of awards we’d receive, the praise from both the military and civilian world, for capturing the “brutality of war” in such an “unvarnished” and “candid” way. “Visceral,” it would be called, “psychedelic.” And our bravery would be lauded as well, for never putting down the camera, for running ceaselessly into the fire. “The brave ones shot bullets, the crazy ones shot film”: we loved that corny slogan from Vietnam, from the glory days of journalism, back when you could actually make a difference just by photographing a napalmed girl or an executed VC. Now there was no difference to make. Pro-war, anti-war—it didn’t really mean anything anymore.

And yet: if our eyes were beginning to become one with our technologies of 24-7 documentation—we had drones and surveillance blimps hovering in the sky that could see through walls, and biometric-analysis tracking systems that catalogued people via retinal scan—and if we were Marines with the gall to film through the scopes of our rifles, then surely something real, something incredible and also educational about war and dying that we hadn’t already seen in the beheading videos they showed us in boot camp, would get captured through the steely lens of our holy death cams. For ComCam kids, the camera was an extension of our rifle, a kill-shot camcorder that doubled as both weapon and cataloger. We dreamed in first-person shooter.

We were eighteen when we enlisted, horny yet abstinent, vile yet pure, impressionable and impenetrable at the same time. You can’t tell an eighteen-year-old nothing, unless it’s something like “Getting shot at is better than sex.” The videos we watched growing up opened a door to the hidden parts of reality, but also distorted it. Internet porn taught us how to fuck while heightening the act to the point of pastiche, so that when we started doing it for real, mimicking the words and sounds and movements, it felt less intimate, less authentic than when we were alone in our rooms. We weren’t just desensitized, we were transubstantiated into a new design, a new frame of looking, feeling, believing. Things happened in videos of real life that could not be explained—a weird blip in the night sky might be a UFO, or it might be an effect of autoexposure. It was hard to process, and left you feeling sort of removed from it all the more inundated you got. The more the world was documented, the less sense it started to make.

***

Stills from accompanying video (below), edited by Miles Lagoze and Eric Schuman.

***

In the end, the only deaths we’d capture were of our own guys, which we never wanted to happen but also secretly needed to happen. To show the cost of war there had to be an actual cost. The stakes of war were such that people you knew would have to die—this came with the cinematic baggage we each brought with us.

One of our first KIAs was not a KIA at all, but a suicide. It happened a couple of months into the deployment, not long after Loya and I were issued the new digital cameras we’d been pining for—we ended up not having to break the old ones; our commanding officer heard that other ComCam guys were breaking theirs, and intervened by switching everyone out. Lance Corporal Laight had a speech impediment, and he kept falling asleep on post. He’d been in Afghanistan before, so he shouldn’t have been fucking up the way he was. After getting hazed by Marines who were technically his juniors, he left a note on his iPhone and shot himself with his M4. His squad leader had chewed him out the night prior to his death.

I remember they didn’t give Laight a memorial while we were in country. One of our duties as Combat Camera was to film memorial ceremonies, where the chaplain would stand up and read off a few Bible verses—they lumped everyone into Christian services—and someone would play “Chicken Fried” by the Zac Brown Band. After we put the packages together, we’d send the videos home to the families.

I was pissed that Laight didn’t get a memorial, because I liked him—he was a goofball and had the face of a little kid, and his presence had a weird, comforting effect; you thought that if he could make it through the deployment, anyone could—and it seemed like they were trying to sweep his death under the rug, or like he didn’t rate a memorial because he hadn’t died the right way. Suicide was so common in the Marines that it became a chore; anytime someone did it, we’d have to sit through a PowerPoint presentation about not killing ourselves, how to spot the signs, ask for help, etc.

After filming a memorial for another guy, who’d died from a sucking chest wound around the same time as Laight, I got called into the office of the Company “Top,” First Sergeant Argon. He had a lazy eye and thought my job as Combat Camera was totally useless: “I could teach a monkey to do your job,” he told me once. He was very intimidating, especially because his lazy eye made it nearly impossible to tell if he was looking at you or not.

“You’re going to the dam,” Argon said.

We’d be on the next convoy through the Sangin Valley, up the rocky slopes riddled with IEDs to the crown jewel on the hill that was, although we didn’t know it at the time, the sole reason our unit was in Afghanistan.

“Why, First Sergeant?” I asked.

“Why do you think? To film something.”

They never told us anything. Secrecy was a currency in the Marine Corps: the higher up you were, the more you knew, and in order to maintain the hierarchy you had to keep the lower-enlisted in the dark.

“Hey, you lazy-eyed fucker,” I wanted to shout. “Why didn’t you give Laight a memorial?”

It wasn’t till we got back to the States that I realized why that would have been a bad idea. If he had killed himself because of how his squad was treating him, would his family really want to see a video of the same guys commemorating him? When we had the final memorial ceremony, back in North Carolina, for all the guys that had died during our deployment, Laight’s photo was up on the stage with the others, and I imagined the pain and confusion his parents must have felt sitting there packed into the assembly hall, enveloped by a sea of his camouflaged killers.

***

***

Loya and I had heard rumors about the dam, and when we got there, after an hour-long ride through abandoned villages and bazaars, we saw that they were all true. The dam was a theme park, a cathedral, a cinema. The views were from another world: you could see the whole war from its rocky slopes—all the mud huts and hamlets our unit was occupying. It was like a Universal Studios ride through a different time, back when Kabul was called the Paris of Central Asia, and Mohammed Zahir Shah, the last king of Afghanistan, used the dam as a resort. He’d bring women to go swimming in its many pools, and get them drunk on wine. It was the only place in our area of operations that had actual buildings as opposed to mud huts, and the chow hall was fully staffed with Marine cooks who had steaks and other goodies flown in to the base. There was supposedly a haunted hotel somewhere around there, where an entire company of Soviet Spetsnaz had been overrun and flayed alive by the mujahideen. Marines would get high on hash and go swimming in the dam’s turquoise waters when the place wasn’t under mortar attack, then explore the hotel.

But the dam was impossible to film. It didn’t look right on camera. You couldn’t capture the weight of it, nor the faint, always present sound of rushing water that crushed everything and expanded it at the same time. Filming at the dam was like holding a camera up to a movie screen.

The first thing Loya and I did, after getting some shitty panorama shots of the place for the intel folks, was seek out our friend Wahid. Wahid was the personal Afghan translator of a colonel who worked at the dam. Like all the interpreters (terps for short), he was working for a visa to the U.S.—an interminable process that you might not outlive, unless someone higher up intervened on your behalf. Wahid’s hope was that the colonel would show his thanks by pushing his paperwork to the front of the pile. And, unlike the other terps, Wahid had already been completely Americanized by U.S. forces. He’d been on nine consecutive deployments with a host of different units ranging from Blackwater to Special Ops. He was also an asshole, and the most anti-Muslim Muslim I’d ever met. He ate pork in front of the other terps, much to their chagrin, and derided the prophet Muhammad. Some months later, after I’d gotten hit with shrapnel from a grenade, he wouldn’t stop flicking me in the head where my bandage was, talking about how many times he’d been shot.

“Americans are fucking pussies, man,” he said. “I’ve been shot twice on two different deployments. Where is my Purple Heart? Where is my PTSD?” We would come back to the States mythologized as traumatized heroes, overmedicalized and treated with kid gloves, free college, and pancakes at IHOP on Veterans’ Day, while Wahid would remain merely a collateral fixture of the place he came from.

We found him serene, almost glowing, in what looked to be an old bomb shelter. He had his own room with a TV, a beautiful rug, and a giant hookah in the corner. The three of us got high and watched live performances of Alizée, the French Britney Spears, who he was obsessed with, off his hard drive. The other terps came and watched us, and Loya started dancing.

“My mom always knew I was going to be a dancer,” he said. “When I was in the womb, I’d always start kicking anytime she played music.”

Then we did the thing we always did for Wahid: romanticize America, building it up to the sublime. The women, we’d tell him. “They’ll sleep with you the first time you meet them?” he asked. “Oh, yes,” we said. The food, the drugs. You wouldn’t believe it. You’re gonna love it. We’d all get so drunk when we got back, we’d die. This was the happiest moment of our deployment.

The next day, they had us film the Afghan engineer who ran the dam, a short man in typical Afghan garb, except for the fancy Warby Parker–esque glasses he wore, which made him stand out. Rumor was that the poor guy kept getting kidnapped by the Taliban and other militias on his way home from work. They would snatch him up and use him as leverage in their attempt to hold sway over the region. Most of the time they’d let him go after a couple days, and he was probably getting a few kickbacks from the various groups as they tried to get him on their side.

There were a bunch of Army engineers putting around, shaking hands with him before the tour started. Then we walked through the innards of the hydroelectric dam, which was like a dementia-ridden brain where antiquated pieces mixed with new ones. The Army guys would stop every now and then and tell me to get a shot of them talking with the guy. It didn’t matter what was being said, just so long as I had B-roll of them gesturing and pointing at stuff. After ten years of trying to fix it, the dam was still broken. It was missing seven hundred tons of cement that U.S. and British forces had been trying to transport there, but we’d kept getting ambushed and blown up by IEDs along the way.

The dam was meant to be our supreme “Sorry for invading you, look, we’re here to help” act of benevolence. It had been built by the U.S. during the Cold War in the fifties, bombed by the Soviets when they invaded in the eighties, left broken for years, and then bombed again by the U.S. immediately after 9/11—and now this unit was trying to fix it. The U.S. military had already thrown close to a billion dollars at the project by the time we got there, most of which had gotten funneled to the Taliban.

The Army guys did the usual song and dance with the engineer, and even drove to his house to sit down and eat some fish that he’d caught in the Helmand River (“shit fish,” someone commented). We met his family, and I filmed the whole thing, like some kind of weird sitcom. It reminded me of detainee reunions, where we’d release the people we’d wrongfully detained and I’d take photos of them being greeted by their families upon their return. I’m sure if the Taliban had Combat Camera, they’d do the same thing for the engineer when they returned him.

When I was done filming the engineer, Loya, Wahid, and I got lost in the dam some more, and sat staring at its rushing water for hours until the moonlight played holochrome with its reflections. We never wanted to leave.

When I got back to the Company, First Sergeant Argon looked at me like I was a fool. I had lost track of how long we were gone; we had been at the dam for over a week when it was only supposed to be a couple days. He told me they didn’t need my bullshit video anymore, that whoever had wanted it—probably in order to get more funding—had already left. Some State Department official. Like most of our footage, it would get archived and then eventually lost.

***

***

Twelve people from our unit were among the hundreds of coalition forces who died trying to fix the dam during the course of the war. I don’t know how many civilians we killed, but I personally saw four who were either caught in the cross fire or mistaken for Taliban. There’s no way to know the number for sure: war is one of the last untouchable spaces where data can never be trusted—especially if it’s our data.

Wahid finally made it to America about a year after Loya and I got out of the Marines in 2012. Within a couple years he hated it and wanted to go back to Afghanistan. He was bogged down by student debt, and didn’t have many friends. American Gen Z students didn’t talk the way Marine grunts did, and the rednecks he lived near thought he was either Mexican or a terrorist. Eventually he was back to praying twice a day like he did when he was a kid, before he was “corrupted by the Marines,” as he’d say.

After the Taliban took over again this past summer, his family had to go on the run. The Taliban knew about Wahid and his work with us, and were leaving death threats. His family were among the thousands trying to flee from Kabul Airport in August. They were almost killed by the suicide bomber who took out 180 people, a few of whom were Marines born after 9/11—the American news kept emphasizing that, as if the war had still been about 9/11 by the time us millennials were there.

“The U.S. abandoned my family,” Wahid texted me.

“That’s what we do,” I replied. I wasn’t trying to sound callous, but he interpreted it as such, and blocked me for a bit.

***

Now I miss the old mini-DV tape cameras. They made the real look dirty, and maybe that’s how it should look. We’ve gotten too comfortable with the real. But I suppose that documentation, like everything, goes in phases. Once you can see the phases, the world loses meaning.

In my Trazodone dreams I’m at the dam—still broken—with Wahid and Loya, and the engineer is there too, and so is crazy Laight. We’re all watching Alizée and waxing lyrical about finally coming to America.

***

Miles Lagoze’s 2019 documentary, Combat Obscura, was made from footage shot during his deployment to Afghanistan’s Helmand Province in 2011. The video below was created to accompany this essay using footage that didn’t make it into the feature-length film, as well as propaganda material produced by the Department of Defense. It was edited by Lagoze and Eric Schuman, who co-produced Combat Obscura.

Miles Lagoze is a Marine veteran, writer, and filmmaker based in New York. His memoir, about filmmaking and his time in Afghanistan, will be published by One Signal/Simon & Schuster in 2022.